As many a keynote speaker likes to remind us, bright kids love to open things up, to take apart alarm clocks and mechanical toys to see what is inside. When I was growing up, my father was working as a biologist at Burger’s Zoo, where they were building an indoor rainforest at a time when other zoos still had a lot of tiles and cages.

I listened intently as the adults around me talked about adaptive behaviour, carrying capacity and ecological succession, and watched fascinated as an infestation of one ant species caused a ripple effect through the network of predators, plants, and prey.

Those of us in mission-driven roles are finding that we are wasting our time and money if we try to approach environmental and inequality problems in our supply chains one by one, as zoos of old without ecodisplays. We just can’t understand systemic problems properly that way. As we look back at 15 years of IDH’s existence, I can frankly say that IDH learned this the hard way.

© Burgers Zoo

© Burgers Zoo

Burgers’ Bush under construction

Interconnected problems in our value chains

Ten years ago, we were working with the floriculture sector to reduce the negative environmental and social impact of flowers produced in Kenya, Ethiopia, Ecuador and Colombia. When we dug a little deeper, it became evident that workers on flower farms and in factories were underpaid. While that fundamental issue remained unsolved, the partnership could not move towards the goals our partner companies had set out to achieve.

Improving individual garment factories

Companies in the apparel sector were urgently looking for ways to protect workers from exposure to hazardous chemicals, and from the risk of factory buildings catching fire or collapsing with workers inside. With a good partnership and some good ideas, one by one, we saw factories becoming safer places to work where workers had their voices heard. But in an industry that employs more than 75 million workers globally, individual factories seemed like a drop in the ocean.

Islands of success in Vietnam’s coffee sector

In Vietnam, when we first tried to make coffee production more environmentally friendly, we and our partners threw our efforts into farm-level sustainability. But even when all the farms in our project area achieved the highest level of sustainability certification, environmental issues persisted. What were we doing wrong?

Complex problems are interconnected

With linear thinking, just as we finish fixing one problem, an even bigger one bursts through further down the line. This is because the problems of soil health, biodiversity and wage inequality are part of complex, interconnected systems. If a strong trend is surging through the system, then even a well-intentioned solution can be washed away.

The beauty of complex systems is that the inverse is also true.

Partnering up for systemic change

In Vietnam, the coffee farms linked up to improve environmental performance. This led to a landscape partnership, which eliminated the use of banned pesticides in pepper production and eliminated herbicide use in coffee production. During COP28 in Dubai this month, my colleagues Tran Quynh Chi and Huynh Tien Dung received a medal from the Vietnamese government for their services to Vietnamese agriculture.

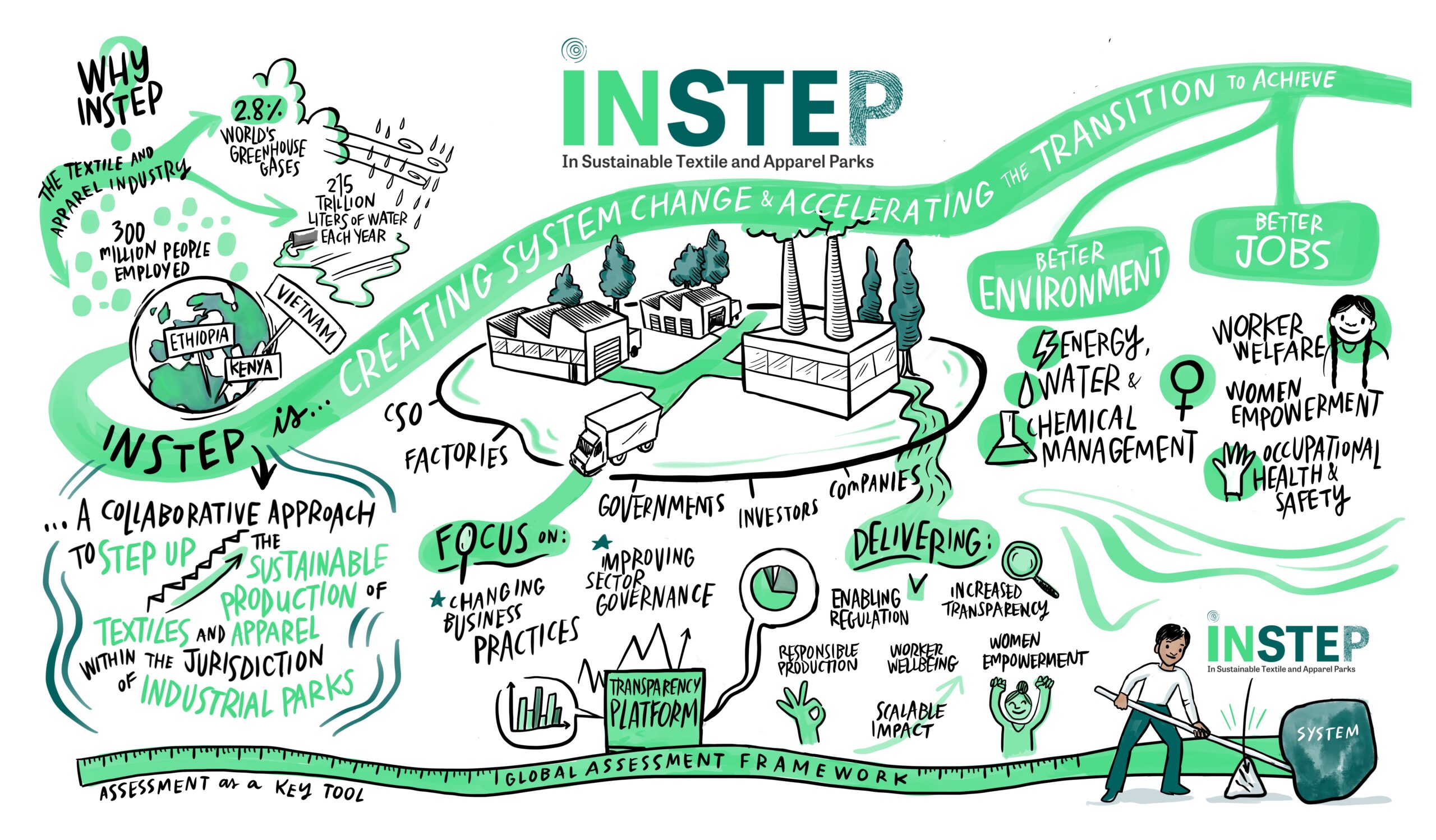

In the apparel sector, we invited partners to cooperate at the level of entire industrial parks. As well as making factories healthier and safer places to work, workers are more engaged, women are more empowered, energy and water use is more efficient, and parks are managing hazardous chemicals more responsibly. Partnerships involving park managers, tenants, local authorities, buyers, and associations are now working together in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Vietnam.

The flower, tea and fruit and vegetable sectors have worked together to create a Living Wage Roadmap. Now 31 companies and organizations are part of our Living Wage Roadmap Steering Committee, a Technical Advisory Group and Stakeholders Committee and companies are using the Salary Matrix to calculate and pay decent wages. On that foundation, they are taking the steps forward that they first wanted to solve a decade ago.

In 2023, it became impossible to ignore how multiple crises are interconnected. In a world where innovation and technology have the power to help so many, it is shocking to see the increase of division, conflict and sheer selfishness unfolding in our markets and in decision-making. Those of us with a role, privilege, ability, and access to influence our global markets have the moral imperative to transform them so that they serve people in society today and the generations that come after us.

© ANP XTRA

© ANP XTRA

Burgers’ Bush today

If we think like ecologists and biologists, we can start to grasp the dynamic and unpredictable currents of climate change, global inequality, and biodiversity collapse. The right drop at the right moment can set off a ripple effect that changes the course of history.